IIHS Crash Test Ratings Explained

New car shoppers should always consider a car’s crash test performance and safety when it comes to making a purchase, but what’s behind those crash ratings?

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety [IIHS] operates independently of auto manufacturers and is funded by the insurance industry to conduct crash evaluations on new vehilces. The folks at the IIHS have quite a few hard-hitting tests that help determine a vehicle’s crash safety. Not only that, but the tests change often in order to improve safety in modern cars.

The IIHS has five different categories for crash tests: front, side, seats, roof strength and collision prevention.

“As we’ve conducted research through the years on how people are injured and killed in real-world crashes we’ve added new tests,” said IIHS senior vice president of communications Russ Rader. “We started the side impact test in 2003, which simulates a crash where the striking vehicle is an SUV or a pickup. Then we started the roof strength test to evaluate how well vehicles protect people in rollover crashes.”

The front, side, seats and roof strength tests are all measured with the same four ratings: Good, Acceptable, Marginal and Poor. Because there are several cars that don’t offer collision prevention, that section has different ratings: Basic, Advanced and Superior.

The IIHS actually features two top ratings: Top Safety Pick, and Top Safety Pick Plus. To achieve a Top Safety Pick, a vehicle must earn Good ratings in the moderate overlap, side, roof strength and head restraint tests, as well as an acceptable or better rating in the small overlap front test.

Those vehicles that have a Top Safety Pick rating can get the Top Safety Pick Plus rating by having a basic, advanced or superior rating for front crash prevention.

Click on to the next page to see how the IIHS determines its ratings.

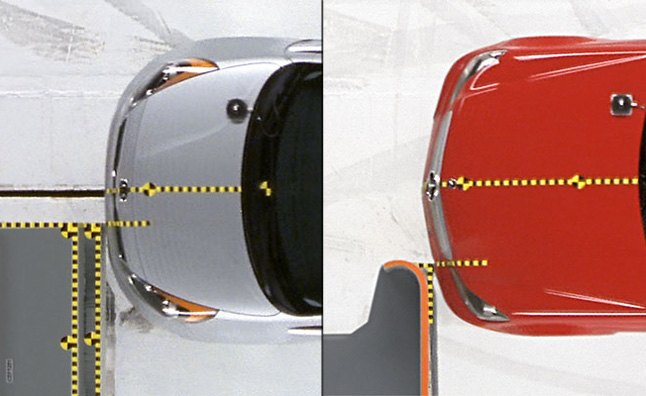

The IIHS performs two frontal tests: the moderate overlap test (top left) and small overlap test (top right).

“The crash tests follow what we’re seeing in the real world,” Rader said. “Frontal impacts, for example, are the most common type of collision in fatal crashes.”

Both tests have adult-sized test dummies in the seats. In the moderate overlap frontal test the car travels at 40 MPH towards a barrier roughly two feet tall. Forty percent of the total width of the vehicle will strike the barrier on the driver side to simulate two cars hitting each other on their driver’s sides.

The small overlap test simulates the car hitting a utility pole, tree, or another vehicle with less contact than the previous test. The car travels at 40 MPH towards a barrier that’s about five feet tall, and the contact occurs at the corner of the car with about 25 percent of the total width hitting the barrier on the driver’s side. This test is a tough one for automakers to prepare for, as the occupants move in two directions: forward and toward the side of the vehicle.

Additionally, the impact at the corner of the car could cause the wheel or suspension to move towards the driver, potentially pushing into the cabin.

“We launched the small overlap front test in 2012 after research showed that about a quarter of the serious injuries and deaths that still occur in frontal crashes are in small overlap collisions,” Rader said.

Data is gathered from these two tests by using advanced crash test dummies that are outfitted with sensors. These sensors can detect the pressure and forces that would be experienced by a human passenger in order to determine what sort of injuries the crash could cause.

Additionally, the dummies are covered in colorful “grease-paint” that spreads to whatever it touches. This allows the crash-test engineers see where and what the dummy is making contact with during a crash. If all goes according to plan, the engineers would only see the paint on the airbags.

Finally, IIHS engineers examine how the vehicles cabin stays intact during a frontal crash. Assessment of the moderate overlap test includes nine areas where the cabin can deform and injure an occupant. The small overlap test looks at 16 areas.

All of these factors are combined to give a rating. According to a study conducted by the IIHS, the driver of a vehicle rated “Good” in the moderate overlap test is 46 percent less likely to die in a frontal crash compared with a driver of a vehicle with a “Poor” rating. Drivers in vehicles with “Acceptable” or “Marginal” ratings are 33 percent less likely to die than in a “Poor” vehicle.

The IIHS also tests how safe a car is when hit from the side. According to the Institute, about 25 percent of accidents involving the side of the vehicle result in a death. This is because there is less area on the side of a vehicle to absorb the impact. Fortunately, the advancement of side airbags and side-curtain airbags have helped keep passengers safer than ever before.

The IIHS’ side crash test is quite severe and involves a 3,300-lb barrier striking the vehicle at a speed of 31 MPH. There are two dummies inside the car both the same size as a small female adult. The IIHS chooses dummies of this size because shorter drivers are more likely to have their heads come into contact with the striking vehicle in a left-side crash.

Ratings are determined for side crashes in a similar way to front crashes. Engineers analyze the data obtained from the sensors in the dummy, observe the greasepaint in the car and study how the cabin’s structure dealt with impact. According to the IIHS’ research, the driver of a “Good” rated vehicle is 70 percent less likely to die in a left-side crash, when compared with a driver of a vehicle that is rated poor. A driver of a vehicle with an acceptable rating is 64 percent less likely to die, while a driver of a vehicle rated marginal is 49 percent less likely to die

The IIHS’s roof strength test is different than the front and side crash tests. The IIHS uses a machine that pushes a metal plate against the roof of the vehicle. The test stops when the roof is crushed by five inches. The force applied to the roof is steadily increasing and is known as the strength-to-weight ratio.

The rating for this test comes from the strength to weight ratio when the roof is crushed five inches. Cars that achieve a “Good” rating feature a strength-to-weight ratio of four, which means that the roof can withstand four times the weight of the vehicle before the roof is crushed five inches.An “Acceptable” rating requires a strength-to-weight ratio of 3.25. A “Marginal” rating is earned with 2.5, while anything below that is considered “Poor.”

The IIHS doesn’t perform rear crash tests, but instead tests how the seats and headrests can prevent whiplash. This is done by using a special dummy with a realistic spine. That dummy is strapped into the seat of the car. But that seat isn’t in the car as you might expect. Instead, the seat is placed on a sled that is moved in a way that simulates rear-impact with a velocity change of 10 MPH, which is equivalent to a stationary vehicle being struck at 20 MPH.

The engineers first assess the seat geometry, ensuring that it lines up with a dummy that represents the an average male adult. For example, one criterion is that the restraint should be at least as high as the head’s center of gravity, or about 3.5 inches below the top of the head. If the seat lines up to the neck, head and torso correctly, it will be given a Good or Acceptable rating.

Seats rated as good or acceptable, are then put on the sled that simulates the rear-end crash. The engineer’s measure the time needed by the head restraint to react to the velocity change and how well controlled the dummy’s torso is when the “impact” occurs. Additionally, the maximum neck shear force and maximum neck tension are measured on the dummy during the test. These forces help identify how well or poorly an occupant’s head and neck would be supported in a rear impact.

All these factors contribute to the rating for the head restraints and seats. An older study conducted by the IIHS determined that drivers of vehicle with “Good” head restraints were 24 percent less likely to sustain neck injuries in rear-end crashes than drivers in cars with a “Poor” rating.

IIHS also tests cars that claim to detect and prevent front collisions.

“These systems are primarily aimed at preventing low to moderate-speed collisions, although many also work at highway speeds and can reduce the severity of a crash,” Rader said.

The test involves an engineer driving the vehicle straight toward an inflatable target that is designed to simulate the back of a car. A GPS system and other sensors monitor the test vehicle’s lane position, speed, time to collision, braking and other data. Simultaneously, an onboard camera captures the test run from the driver’s perspective and monitors any warnings issued by the front crash prevention systems.

This test is done at two speeds: 12 MPH and 25 MPH. Points are awarded based on how well the automatic braking system slows the car in each test, while an additional point are available for having an adequate warning system. Vehicles can earn a maximum of six points for front crash prevention. Vehicles that get just one point earn a “Basic” rating while an “Advanced” rating requires two to four points. Finally, a “Superior” rating requires the full six.

There’s no doubt that the IIHS will make its top ratings tougher to attain, which will spur automakers to manufacture and design safer vehicles.

“We have gradually made the criteria to earn Top Safety Pick tougher over time, and that will continue,” said Rader. “Eventually, vehicles will have to earn a “Good” rating in the small overlap test to qualify for the highest award and we expect to tighten the requirements for front crash prevention performance as well.”

Rader also said technology, like front collision prevention systems, is proving to be effective at reducing accidents and collisions and that there may be more tests that involve safety technology in the future.

“The goal is to encourage the highest level of crashworthiness performance and to drive the wider availability of the most effective crash prevention systems.”

While the IIHS’ tests are robust, they aren’t the only authority when it comes to assessing the safety attributes of new cars. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) also puts new cars through a suite of crash tests and provides their own ratings as well.

Called the New Car Assessment Program (NCAP), NHTSA’s tests have specifics and rating all of their own, but rarely do they contradict what the IIHS finds. Looking at ratings gathered from both organizations will help you understand how safe, or unsafe your potential new car will be.

Sami has an unquenchable thirst for car knowledge and has been at AutoGuide for the past six years. He has a degree in journalism and media studies from the University of Guelph-Humber in Toronto and has won multiple journalism awards from the Automotive Journalist Association of Canada. Sami is also on the jury for the World Car Awards.

More by Sami Haj-Assaad

Comments

Join the conversation