What is a Hybrid?

The model year 2000 marked the beginning of hybrid vehicle sales in the U.S., today there are 41 hybrid passenger cars, trucks and SUVs on the market, but for those just learning about them, consider this an introduction.

In essence, a hybrid is an otherwise ordinary vehicle that’s distinguished by its powertrain – or, what makes it go.

Some hybrids are dedicated as hybrid only – like Toyota’s Prius line, or Ford’s C-Max – and others are variations of conventional vehicles albeit with gas-electric powertrain – like the hybrid versions of the Ford Fusion, Toyota Camry, or Honda Accord.

According to Webster’s Dictionary, one definition for hybrid is “an offspring of two animals or plants of different races, breeds, varieties, species, or genera.”

Aside from the fact that a hybrid vehicle is manufactured – not an organic creation – this definition gets to the heart of the matter.

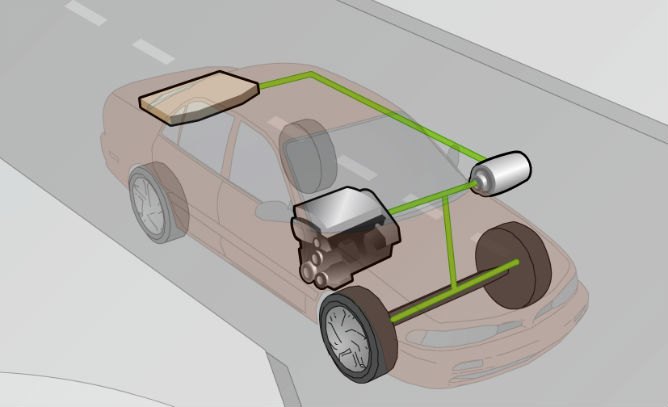

A hybrid vehicle utilizes two different powertrain “varieties” – or energy sources – and merges them to form one hybrid powertrain, and this is a simple definition for a hybrid vehicle:

Definition Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV): A car, truck, SUV, or other type of vehicle that is propelled by more than one power source mated together to work in conjunction.

Hybridization is typically between only two different power sources – not three or more – and in the U.S. these are a gasoline engine paired with electric motor(s).

In Europe there are also diesel-electric hybrids, and theoretically, one could merge any other power source, such as a natural gas engine and electric motor to make a CNG-electric hybrid, although to date none are on the market.

Actually, fuel cell electric vehicles like those being introduced by Hyundai, Toyota, and Honda are forms of hybrids in that they merge battery-electric and hydrogen fuel cell propulsion.

There are several different sub-types of battery-based hybrid personal passenger vehicles such as “mild hybrids” and “full hybrids”.

Why a Hybrid?

As you may have heard, added complexity – such as from two different powertrains – potentially means there’s “more to go wrong” but hybridization is being used for automobiles anyway.

Why? First off, the maintenance, repair, and resale value record for hybrids have been better than some early voices prognosticated –i.e., in many cases, hybrids have fared well – and secondly, hybrids merge the best of two worlds for an elegant solution.

From the “world” of internal combustion engines, a hybrid’s gasoline-powered engine provides high power-to-weight, especially suitable for quick acceleration and higher speeds.

Also, there’s no range anxiety as hybrids fill up at the pump just like conventional cars. This means if you can already drive a car, you don’t really need to learn anything new to adapt to operating a hybrid. Granted, an easygoing driving style yields better mpg, but it is not required.

The best hybrids use the more efficient Atkinson cycle which modifies when air is let into the combustion chamber. It’s a variation of a traditional four-stroke engine and is more fuel-efficient, a bit less powerful, but an electric motor makes up the difference in reduced power – leading us to the second half of the hybridization.

From the “world” of electric power, hybrids benefit from electric motors which provide 100-percent torque from standstill and do well at lower speeds while emitting zero exhaust emissions and burning zero gas. At parking lot speeds, and particularly during stop-and-go traffic, hybrids may whir along like electric cars.

Even at up to highway speeds, the best hybrid systems may alternately use electrical power when low-energy demanding conditions permit.

Behind the whole hybrid system are computerized controls that monitor how much power is needed, and choose to teeter between pure electric power, or gasoline power, or both.

Bear in mind – particularly in “full hybrids” and not just those with a “helper motor” added to an already self-sufficient gas engine – that neither the electric motor or gasoline engine is ideal to propel the hybrid by itself in all conditions. At times one or the other will be used, but the idea is like a tag team where the best power source for the job is utilized and the transitions are often imperceptible, but visibly displayed on the car’s instruments. And alternately the motor and engine can act as a team for full “system power.”

Hybrids also typically employ “stop/start” technology which simply means the engine shuts off when the car stops – either at a light, stop sign, or when parked. Releasing the brake typically restarts the engine almost instantaneously.

On the go, the gas engine recharges the battery pack – thus no need (or ability) to plug in – and regenerative braking also recharges the pack by using the electric drive motor as a generator when the driver’s foot is off the accelerator while coasting, or during actual braking.

Most hybrids use a recyclable battery pack in addition to the usual 12-volt lead-acid battery. The rechargeable propulsion battery is often nickel-metal hybrid, and some are lithium-ion as the industry is leaning toward these lighter, more energy-dense batteries.

Hybrids, with the exception of those with automatics from Hyundai, Kia, Volkswagen, Audi, and perhaps a couple others, usually use a Continuously Variable Transmission (CVT).

This is a kind of automatic transmission that optimizes engine speeds for maximum efficiency.

Hybrids also typically use electrically driven accessories for the air conditioning system, power steering, and braking.

The answer to “why a hybrid” can be answered in one word: efficiency.

As long as electrical energy is being relied upon this helps increase the average mpg and cut greenhouse gas emissions.

And sure enough, the best hybrids surpass the best conventional vehicles’ mpg by a reasonable margin.

The most efficient non-hybrid – a relatively tiny, lightweight Mitsubishi Mirage hatchback – is rated 37 mpg city, 44 highway, 40 combined. That’s pretty good, but the larger, safer, (and more expensive) mid-sized Toyota Prius Liftback is rated 51 mpg city, 48 highway, and 50 combined.

What a Hybrid is Not

Although certain types of hybrids may do a passing imitation of electric vehicles, they are not to be confused with EVs.

Electric cars have simplified powertrains centered around their much-larger lithium-ion battery packs, motor(s) which also generate electricity back to the pack along via regenerative braking, and they all plug in.

There is a type of hybrid that does plug in – the “plug-in hybrid” – and by virtue of its larger-than-usual-hybrid sized battery that is still smaller than a pure EV’s, it can drive longer on ell-electric power – typically from 11-38 miles depending on model.

But otherwise, hybrids are distinguished from simplified EVs which typically do not even have a multi-speed transmission.

What Hybrids Are Available?

The bestsellers are the ones that most closely fulfill hybrids’ reason for being in the first place – relative fuel savings for money spent.

With government efficiency rules ratcheting up the pressure, and the cost of gas increasing as well, more hybrids are on their way and as a type, they remain relevant alternatives – measured compromises that among the best of the type, do pay off.

Become an AutoGuide insider. Get the latest from the automotive world first by subscribing to our newsletter here.

More by Jeff Cobb

Comments

Join the conversation