Why Your Next Set of Tires May Be Made From Weeds

When it comes to the auto industry, oil isn’t the only thing imported from foreign countries and subject to supply issues and price spikes. The same is true of the rubber in your car’s tires, though a solution could lie in a simple, resilient weed that grows freely across the American southwest.

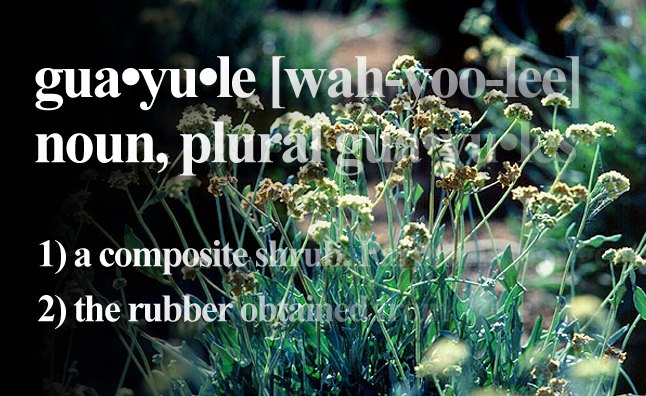

GUAYULE 101

The guayule plant (pronounced wah-yoo-lee) is a scraggly bush that thrives on marginal land in desert areas like the American Southwest and Mexico. This unassuming perennial shows amazing promise as a source of natural rubber. Tire makers are scrambling to figure out how to transform it into a commercially viable alternative tree-sourced latex.

These traits give the difficult-to-pronounce but intriguing guayule shrub some big advantages over the hevea (huh-vay-uh) tree, today’s biggest source of latex.

“The natural rubber tree is tapped kind of like maple trees to make maple syrup,” Yurkovich said. The bark gets slashed and the sap collected. But these trees take about seven years before they can produce latex. Guayule is ready to harvest in as little as one or two years.

According to Bill Niaura, Director of New Business Development for Bridgestone, “there are hundreds if not thousands of plants that make natural rubber.” But he says the hevea tree, which are native to Brazil, is the most productive and guayule is “second in line,” another reason companies are researching it. According to Niaura, “we believe that guayule is the one that holds the highest potential.”

Another problem with the hevea tree is that the industry only has one source of latex. “Seventy percent of the world’s supply of natural rubber comes from Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand,” Niaura said. Ominously, Yurkovich echoed this issue “production is going down” and “there is a looming shortage of natural rubber.”

Yurkovich also mentioned demand for natural rubber is growing “exponentially” in China and India, and that today’s producers of the material can do other things more profitably, like growing food or even illegal drugs on land that would otherwise be devoted to hevea trees. These are two factors reducing the supply of natural rubber and spiking its price. Higher costs are forcing tire makers to look for other sources of the mandatory material. The advantages of a secure, affordable, domestic supply of latex are obvious.

The idea of extracting rubber from the guayule bush is not a new idea. Niaura said indigenous people have known about the plant for hundreds and possibly thousands of years. Even the U.S. government was looking into it during World War II. Yurkovich said they produced experimental guayule-based tires around 1942, but the project never got out of the prototype stage.

Bridgestone has been involved with guayule since the 1980s. Niaura said “it really is a new look at an old idea.”

FROM RESEARCH TO THE REAL WORLD

Additionally, Cooper Tire has partnered with another outfit called Yulex, a leader in guayule-based technology. They make all kinds of different rubber products out of the desert-dwelling bush, from wetsuits and lineman’s gloves to medical supplies and yoga mats.

“What we are seeking to do is not just put a little bit of (guayule) latex in a tire and say ‘a ha, it works.’ What we are actually trying to do is replace all of the natural rubber in tires,” Yurkovich said. He also said “nobody has been able to totally eliminate it (natural rubber).”

Latex has a lot of advantages over synthetic substitutes. It has very good heat resistance; it weathers well and can be mixed with variety of other materials. And according to Niaura, “as you get to tires that experience more extreme conditions natural rubber becomes more important.” This is why tires on tractor trailers and aircraft have a higher percentage of latex in them than passenger-car tires.

FROM FARM TO FREEWAY

After a year or two of growth the guayule plant can be harvested – chopped of right at the base since it grows back. It then gets ground up and the latex extracted. Of course the rubber cannot be used as-is, extensive processing is required and additives like silica, carbon black and other polymers have to be incorporated.

Aside from a secure source of an important strategic material, a thriving guayule industry has the potential to create many domestic jobs. “At a high level you turn desert wasteland into productive farmland,” Yurkovich said, plus more jobs can be created for people in the transportation sector and at processing facilities.

COMING TO A STORE NEAR YOU

Given the promise of guayule, Cooper Tire is not the only company researching it. Bridgestone, the world’s largest tiremaker is looking to turn this native species into a commercial crop. The Japanese firm is operating a 281-acre agricultural research site in Eloy, Arizona, located in the south-central part of the state. Since the plant grows in desert areas “we’re not looking at displacing food crops” Niaura said, a controversial issue when talking about corn-based ethanol.

“Our objective here is to bring something to market as fast as we can,” and according to Yurkovich, “Cooper is very fast at what it does,” since it’s not as big as companies like Goodyear. He also said “we’ve got a pretty good head start on anybody else that’s taking a look at this.” Guayule-based tires could become available in as little as five years.

Bridgestone too is hard at work. “We’re focused on not just the process . . . but we’ve got an equal effort on the agricultural side,” Niaura said. They’re trying to get guayule accepted in America’s agricultural system, which is not necessarily an easy task.

Tiremakers are constantly fighting raw-material costs from oil-price spikes to the availability of natural rubber. Guayule could give them a constant, stable, secure source of strategically important latex. Who would have thought a scrubby desert weed could be the answer to combating rising rubber prices and an impending global shortage of a product we all use to get us where we need to be.

Correction: Heavy-truck tires are comprised of 40 percent natural rubber by weight, which is different from latex. Also, the Department of Energy (DOE) was not involved in the $6.9 million grant provided to Cooper Tire.

Born and raised in metro Detroit, Craig was steeped in mechanics from childhood. He feels as much at home with a wrench or welding gun in his hand as he does behind the wheel or in front of a camera. Putting his Bachelor's Degree in Journalism to good use, he's always pumping out videos, reviews, and features for AutoGuide.com. When the workday is over, he can be found out driving his fully restored 1936 Ford V8 sedan. Craig has covered the automotive industry full time for more than 10 years and is a member of the Automotive Press Association (APA) and Midwest Automotive Media Association (MAMA).

More by Craig Cole

Comments

Join the conversation

You need a fact check There is a huge over supply of rubber and the market price is way down as it stock piles up